On the anniversary of D-Day, Simon Lebus delves into our archives to understand the challenging circumstances some of our past candidates sat their exams under, from the Home Front during World War II to internment camps in Singapore.

Summer has arrived at last and with it those perennial seasonal fixtures of hay fever and exams, a bad mixture for those unlucky enough to suffer from both. This year the month of Ramadan, during which Muslims abstain from food and drink during daylight hours, also coincides with the exam season, creating some concerns about whether fasting students too will find their exam performance affected.

These disruptions, however, are as nothing compared to some of the difficulties faced by candidates in times of war, and to coincide with the anniversary of D Day which falls this week, we have been researching our archives to find out a bit more about how these were managed.

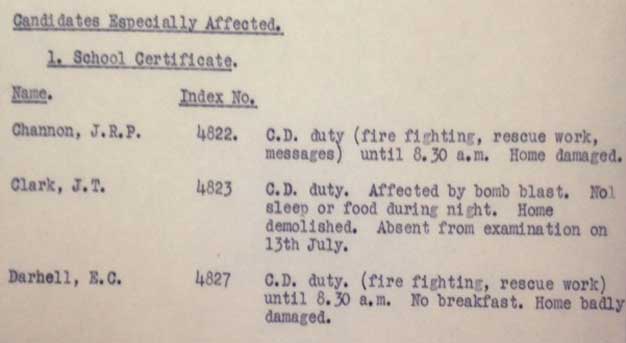

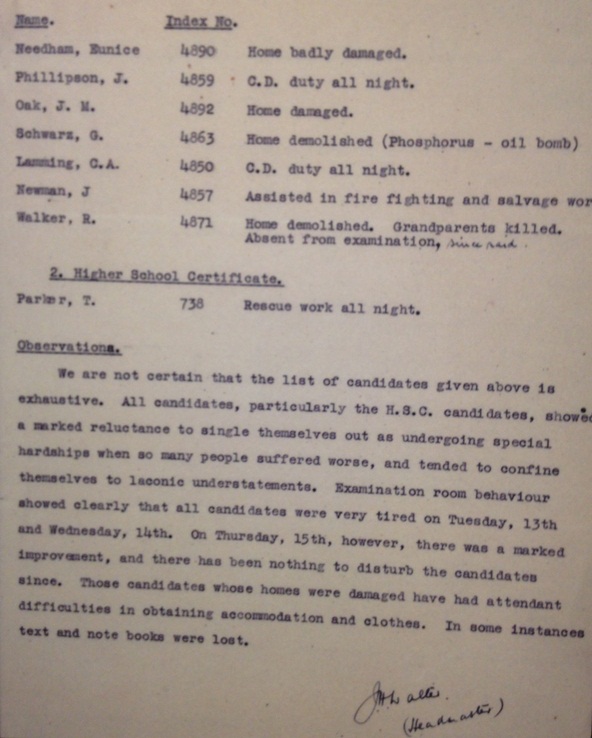

The main challenge for exams on the Home Front was probably air raids. As might be expected with public exams, where there is always a high level of procedural prescription, emergency exam regulations laid out procedures for how invigilators were to respond if candidates had to be evacuated to air raid shelters mid-exam, clarifying in particular that "every effort should be made to avoid them discussing the examination (whilst in the air raid shelter)". Of course outside the exam room air raids were the cause of death, destruction and mayhem and the image below movingly records details of several candidates for whom 'special consideration' (the process by which an allowance is made in marking for any adverse circumstance suffered by a candidate that might directly affect their exam performance) was applied because they had been involved in firefighting and rescue work, or suffered the loss of their homes or members of their family.

As might be expected, candidates attempting to sit exams during this time could be badly affected, and the Headmaster of a school in Grimsby sent a report (shown below along with a list of further candidates badly affected and entered for 'special consideration') after what was officially described as "a sharp raid" in July 1943 (the heaviest that Grimsby had yet suffered) stating that "All candidates suffered considerably from fatigue and nervous strain …with some very badly shaken and distressed. The fatigue and nervous strain were increased by an 'alert' and gunfire the following night" when neighbouring Hull was bombed. With a telling insight into the spirit of the times, the Headmaster also notes that "all candidates… showed a marked reluctance to single themselves out as undergoing special hardships when so many people suffered worse, and tended to confine themselves to laconic understatement."

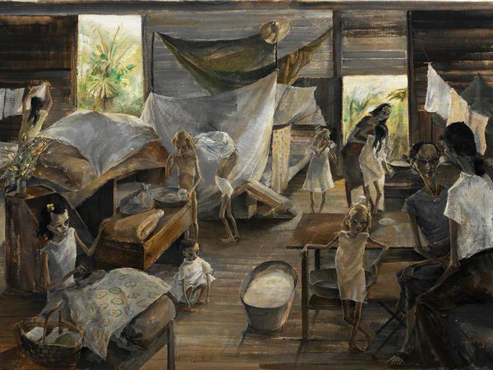

This spirit was also very much in evidence in Singapore. Overseas sessions for Cambridge exams had been suspended from summer 1940 onwards but in the Sime Road internment camp (pictured below in a painting by Leslie Cole) schooling continued to be organised for children, though it was suppressed by the Japanese between October 1943 and July 1944 following a sabotage incident for the organisation of which the Japanese believed the school had served as cover

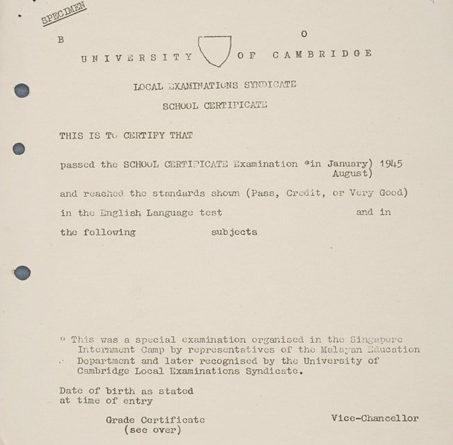

The inspiration behind this was the redoubtable H.R. Cheeseman (pictured right), Camp Education Officer at Changi Prison, who had been Deputy Director of Education in Malaya at the time of the Japanese invasion and was responsible for the introduction of Scouting to Penang and for making English a compulsory part of the Malay school curriculum. Conditions were very tough, with few teaching resources available, but qualified instructors were found from among the inmates in most subjects. Astonishingly, in the circumstances, they managed to prepare a small number of candidates for unofficial examinations at School Certificate level (equivalent of GCSE) which were set and marked by the camp’s instructors. Scripts from these (and similar exams taken by internees in camps in Shanghai) were scrutinised by examiners after the end of the war, following which they received official recognition by the Cambridge Syndicate at the end of 1945 (an example pictured below.)

Camp Education Officer at Changi Prison, who had been Deputy Director of Education in Malaya at the time of the Japanese invasion and was responsible for the introduction of Scouting to Penang and for making English a compulsory part of the Malay school curriculum. Conditions were very tough, with few teaching resources available, but qualified instructors were found from among the inmates in most subjects. Astonishingly, in the circumstances, they managed to prepare a small number of candidates for unofficial examinations at School Certificate level (equivalent of GCSE) which were set and marked by the camp’s instructors. Scripts from these (and similar exams taken by internees in camps in Shanghai) were scrutinised by examiners after the end of the war, following which they received official recognition by the Cambridge Syndicate at the end of 1945 (an example pictured below.)

Natural disasters, like the Nepalese earthquakes or the Icelandic volcano eruptions can and do still cause problems, but most special consideration nowadays is a result of illness or individual misfortune. Of course, that is little consolation for the affected candidate, but the rest of us can count ourselves lucky never to have experienced the wholesale disruption described above and all of us can admire the astonishing spirit and tenacity with which teacher and pupil alike managed to cope with it and pursue their education regardless.

Simon Lebus

Group Chief Executive, Cambridge Assessment

The image seen at the top of this page is not sourced from our archives; it depicts school children entering an air raid shelter in Gresford, Wales.