Reform of secondary education in England has been a topic of great attention over the past few months. Many of those calling for change have suggested scrapping A Levels, often in favour of alternatives that are described as ‘baccalaureate-style’ systems. The proposals and their rationales vary, but some argue that students are being asked to specialise too early in their education. Others believe a more ‘holistic’ or ‘well-rounded’ curriculum is necessary to better balance academic, technical and applied education and ‘create a level playing field between different pathways for young people’. What these arguments have in common is a notion that students currently have limited choice post-16. But is that true?

Allowing student choice increases the intensity of learning, which is good for them, good for society and good for the economy.

Before we look at the full range of choices, let’s just think about what kind of choice we have, and need. By 16, many young people want to focus on things which they enjoy studying, and do well in. Allowing student choice increases the intensity of learning, which is good for them, good for society and good for the economy. It’s one of the key things on which economists and educationalists agree. And A Level allows exactly that choice – for both those who want to really specialise and for those who, conversely, want some ‘subject spread’. The top combination of A Levels remains maths, chemistry and biology, and that combination is taken by only 8% of A Level candidates. We stopped counting at well over 10,000 combinations of subjects. And that’s not including the mix of types of qualifications we explore below. And we’ve looked at ‘space’ in 16-19 programmes too. Although three A Levels are considered a full-time programme, there’s enough space and time to include additional supplementary study and activities – the kind of flexible curriculum enrichment which commentators call for.

A Levels have been an extraordinary national success, and many students see them as their preferred route through to further, more specialised study. They have long been called ‘gold standard’ qualifications and (in the restrained language of an official body) compare favourably with qualifications studied internationally in terms of depth and breadth of content covered.(1) But they are not the only option for students at this age in England.

A Levels have been long-lived and valuable precisely because they have repeatedly adapted to changing educational and social needs over the past 70 years. That evolution has occurred in the presence of a wide range of other qualifications, some of which have not stood the test of time, often for a variety of reasons.

Currently, students in England can study A Levels, Applied Generals, other vocational and technical qualifications, as well as new T Levels and apprenticeships. While it is true to say some students focus on A Levels, others take a combination of qualifications that reflect their interests that then feed into specialist higher education, other studies or employment. Indeed, studying a combination of qualifications alongside A Levels has been beneficial to widening participation and has been a key route of growth for students entering university over the past 10 years. So, the opportunity to study a broad and balanced curriculum post-16 in England, with opportunities for work experience and employer engagement, already exists.

What if we scrapped A Levels?

If complementing A Levels with a range of other high-quality qualifications has been the direction of travel in recent years, would there be any significant issues with removing A Levels from the mix? There are several, including:

1. A Levels in England feed into an already specialised higher education system, which means students often study for just three years at university. Any move to more generalised education post-16 may mean longer study at university, like with other systems around the world. Given there would be an additional cost associated with this, who would pay? Students and their parents?

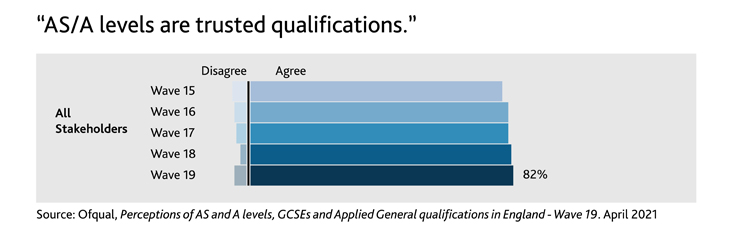

more than 80% of stakeholders say A Levels are trusted qualifications and are good preparation for further study.

2. Removing A Levels would not necessarily deliver a range of qualifications that are considered to be of a similar standing with stakeholders at home or internationally. Ofqual recently published data that shows that more than 80% of stakeholders say A Levels are trusted qualifications and are good preparation for further study.(2) Reputations are hard to forge, and it would seem more logical to try and level-up other qualifications with A Levels, rather than remove them in the hope of establishing new or different opinions, building on the success of the current system?

3. Just as we believe restricting student choice to only A Levels is inappropriate, so too would it for students not to have the choice about whether they specialise sooner rather than later. The current system in England allows a great deal of flexibility for students and teachers to decide what is appropriate for them and their ambitions. In many ways a ‘baccalaureate-style’ system represents compulsory breadth, when many students want to specialise. The issue of breadth in England 16-19 is far more of a curriculum issue than a qualifications issue. Start looking, and you find exams in many systems which correspond to A Levels in ours. Really, this breadth issue is about who insists on breadth and how it's funded and resourced. A Levels are very like the three or four exams which German and Finnish students take 16-19, it's just that students study more non-examined subjects in those nations. Who chooses, and how many....those are key curriculum decisions, for society to discuss and resolve. Flexibility is a quality often cited in ‘baccalaureate-style’ systems, but we need to be clear that it exists already in the current system – which often is not recognised, and our research makes clear.

Flexibility is a quality often cited in 'baccalaureate-style' systems, but we need to be clear that it exists already in the current system.

4. It is important to say that teachers tell us the last thing they want at the moment, while they’re dealing with recovery learning after coronavirus, is a big shake-up of the education system. So, while there is always merit in rethinking assessment, we believe we already have a post-16 education system that delivers much of what would be hoped for from a ‘baccalaureate-style’ system, while retaining our ‘gold-standard’ qualifications that stand-up so favourably around the world.

Just as they have done for many decades, A Levels can continue to evolve over the coming years, driven by the very best evidence about quality. That is one of the reasons why Cambridge Assessment has launched a set of outline principles that are rooted in research and we believe will help all those interested in the debate over the future of teaching, learning and assessment.