Crisis seems to breed an uncomfortable mix of wildly opportunist comment and thoughtful reflection. We need to be clear which is which.

‘Driven by the science’ has entered popular discourse, and rightly so. This conviction is embodied in our principles for the future of education and has been the basis for all our previous blogs and papers in this space: strong evidence for change is essential. ‘Look before you leap’ is a more than sensible adage in many fields. In the formation of social policy - including education - there are many voices raised about ‘what’ but few about the processes of change. But the ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘when’ of change are intimately connected. As we will see, looking at the processes of change also helps with better determining what we should do.

‘How’ should we reform education? – change in the right way

Education policy in England is littered with short-lived, poorly-designed solutions which failed to address key problems in arrangements. Remember Individual Learning Accounts? Diplomas? Learning and Skills Councils?

A little known but extremely powerful framework exists for understanding why some ‘panaceas’ turn out to be damp squibs. Failing to understand the nature of genuine problems and differentiating real problems from false errands is central to this framework.

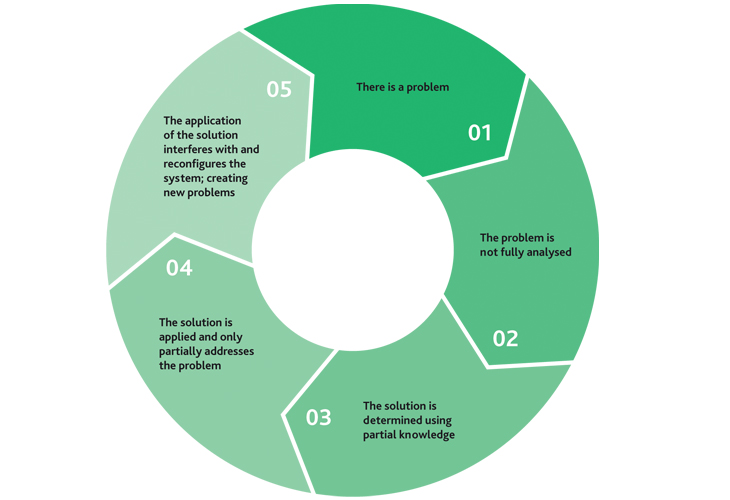

Frank Achtenhagen’s ‘Cycle of Planned Failure’(1), presented back in 1994, provides essential pause for thought. I’ve emphasised his work over the years and would commend reading the full paper to all those interested in educational reform(2). But a simple summary is this :

"Premature action runs very great risk, since it not only can be an inadequate response to the real causes of poor performance - but also, by being enacted it can affect the system, creating new problems rather than remedying existing ones".

Achtenhagen’s powerful model suggests this cycle is all too evident in many nations’ educational policy-making. The cycle identifies the problem, which is not fully analysed and the solution is based on partial knowledge and doesn't fully address the problem and when it is applied creates new problems.

We need to avoid going round and round the cycle. It may seem a bit abstract, but we have seen the practical damage wrought by this dysfunctional, wasteful cycle in too many places at too many times. There are many instances of nations constantly changing their national curriculums when it is other factors and instruments which need attention in order to tackle serious issues of quality at school level.

The problem is that new policy formed in error transforms the system, while not addressing the underlying problems. Attempts to address symptoms, rather than providing solutions grounded in well-considered diagnoses, can rip capacity out of any system, as educators strive to make things work and conform to requirements and regulations. The good news is we already know the means of avoiding or breaking this cycle. We need to:

When are we in need of reform? – change at the right moment

Are we at a point where we can truly identify the nature of the problems we will be experiencing post Covid-19?

An essential question right now is, are we at a point where we can truly identify the nature of the problems we will be experiencing post Covid-19? After all, we are still deep in a global pandemic, with all the social, political and economic implications which flow from that. We still have not fully understood the implications – teacher workload, equity, fairness – of qualifications derived through teacher assessment. We are preoccupied – understandably – by the double-edged effects of remote learning: assets of flexible and engaged working, combined with evidence of worsening equity.

For those who are focussed on assessment, it’s just not yet clear whether removing exams increases or decreases pupil stress and well-being. With this, we are starkly confronted by the lack of resilience of existing exam arrangements and the need for means of collecting dependable evidence on a continuous basis, usable when exams cannot be held. These are very much on our minds.

We need to take Achtenhagen’s advice, to stop and reflect on the competing evidence, and drill down to really robust understanding of challenges and problems.

New GCSEs and A Levels were introduced only a matter of a few years ago and were developed through wide and prolonged consultation and public discussion. Like the best policy in this nation, they enjoy public consent and were developed through transparent, participative processes. These qualifications help specify the content of learning programmes, the depth of treatment of topics and the standards expected. We must not forget that – unlike a very large number of nations, including Finland – England enjoyed improved outcomes in PISA 2018. The well-grounded initiatives on maths and reading in primary are working. And we finally have a wider range of high-quality vocational qualifications and apprenticeships that are beginning to provide a new vocational route. Reform has only just occurred here in England.

What areas of education do need reform? – change in line with clear diagnosis

Prior to pandemic we definitely were doing some things well here in England. But alongside this, and in line with Achtenhagen’s call to action, we need to catalogue the genuine problems in the system the lack of structure and pupil progression in KS3; the reducing but continuing low attainment of too great a number of pupils in reading, writing and maths at the point of transition to secondary education; the lack of development of a mass participation and high quality employer-based vocational route; the extent to which equity is compromised by the continuing impact of social background on attainment; the large number of pupils with poor maths attainment at 16. These were priorities going into pandemic, and some – such as the equity issue – have been exacerbated by pandemic.

If reform leaves the real problems in our educational system untouched, we will have done young people a huge disfavour and bogged teachers down in wasteful effort. Given this understanding of successes and problems in our system, it’s just not clear how some of the putative ‘system changes’ genuinely will help tackle them. The changes will be expensive, resource hungry and disruptive – like all major change. And if reform leaves the real problems in our educational system untouched, we will have done young people a huge disfavour and bogged teachers down in wasteful effort.

This is not a call for inaction. Far from it. Achtenhagen helps us see where we should direct our energy. For sure we need to look at resilience in exams, the balance of forms of assessment, student well-being and the way in which we report attainment. But moving prematurely to major system reform would be a huge mistake. We should really be very cautious about formulating new arrangements before we know what the post pandemic world and education scene looks like. We need first to understand the real character of remote learning and of the novel national assessment arrangements, and work out the means of establishing stable national standards. Let’s avoid the cycle of planned failure, not lapse into it.

About the author:

Tim Oates CBE has been the Director of Assessment Research and Development at Cambridge Assessment since he joined the organisation in May 2005. Previously he had been the Head of Research and Statistics at the Qualifications and Curriculum Agency for the best part of a decade. In 2011 he Chaired the Expert Panel as part of the Department of Education's National Curriculum Review. Tim was awarded CBE in the 2015 New Year's Honours for services to education. Read Schools Week's profile of Tim.

References:

1↩ Achtenhagen, F. (1994) Presentation to Third International Conference of Learning at Work. Milan, June 1994.

2↩ Oates, T. (2017) A Cambridge Approach to improving education. Cambridge Assessment.