Grades are a constant presence in education. From early school reports to qualifications like GCSEs and university degrees, they remain one of the most familiar tools used to report student achievement.

In this second post of a four-part series, James Beadle, Senior Professional Development Manager, The Assessment Network, explores the important role grades continue to play in education today, as well as explaining alternative ways to report student performance.

The value of grades in assessing performance

"Grades help communicate outcomes in a clear and structured way to the many stakeholders of the assessments."

As described in this previous blog from Cambridge, grades are used widely around the world. Examples include A-levels, IGCSEs, International Baccalaureate, Advanced Placement in the United States and the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (Malaysian Certificate of Education).

In each of these systems, grades help communicate outcomes in a clear and structured way to the many stakeholders of the assessments.

For those of us involved in assessment, one of the most important questions we can ask ourselves is: What exactly is it that we are trying to measure, and how are we going to use these measurements?

Sometimes, we might be carrying out a binary measurement:

- Is this person able to drive a car?

- Does this person have a sufficient understanding of workplace safety?

- Has a student reached the required national standard in phonics?

In such situations, we only look to determine a single level of performance (is it satisfactory or not) and can simply use a pass/fail system to report outcomes of our assessments.

Frequently in education, we are interested in not just indicating whether students can or cannot do something. We want to measure how well someone can carry out a specific task, or what level of analysis they can apply to an area of knowledge.

For example, if the results of our assessment are being used for selective purposes, such as access to university or future employment, then we often want to compare candidates with each other - to determine who is most suitable.

Grades can support this by representing different levels of performance. A student who receives an A grade is expected to show stronger understanding or more advanced skills than a student with a C. Grade descriptors like those published by Ofqual help define these levels, bringing meaning to results and supporting fair comparisons.

Why not just give numerical scores?

"The issue is comparability. Students sitting different versions of a paper may experience varying levels of difficulty."

You might wonder why we do not simply report the number of marks a student achieved. We could attach a performance descriptor to each range of scores, e.g., "candidates with scores of 60–70 have the following knowledge and skills…". Would that not be simpler?

The issue is comparability. Students sitting different versions of a paper may experience varying levels of difficulty. Without pre-testing every question, we only understand the difficulty once many students have taken it. To maintain fairness, grade boundaries can be adjusted so that a slightly harder or easier paper does not unfairly impact outcomes.

In such cases, grades give a more stable and comparable indication of performance than raw numerical scores.

What are the challenges with grades?

"Students can achieve the same grade in different ways."

Grades can be a good way to summarise performance, but they do have limitations. One issue is that students can achieve the same grade in different ways.

Imagine two students both achieve a grade 6 in GCSE Mathematics. One may have excelled in algebra, while the other performed strongly in statistics. Although their grades are the same, their strengths are different. A grade alone cannot always reflect these differences.

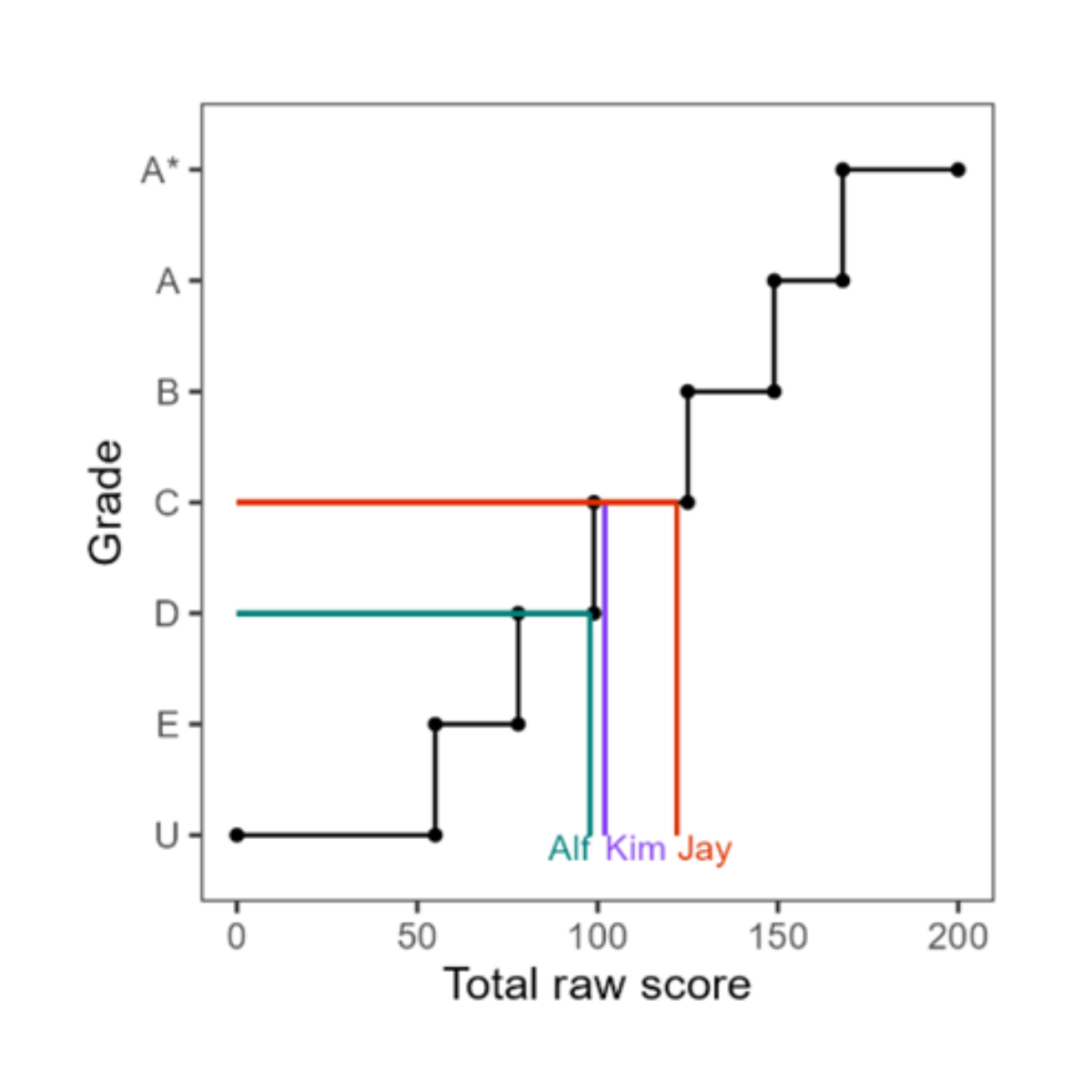

Another issue is the precision of grades (see graph below). View scale score precision diagram (PDF)

Adapted from ‘The case for scale scores – reporting outcomes in the reformed GCSE’ Tom Bramley (2013).

- Alf scores 59 and receives a grade D.

- Kim scores 60 and earns a grade C.

Their performance was nearly identical, but the grades suggest a bigger difference than exists.

Now imagine Jay scores 68 and also receives a grade C. Jay has performed significantly better than Kim, but this is not reflected in their grade. Are we confident that Jay and Kim have delivered the same level of performance?

This does not mean grades are inaccurate. It simply highlights the importance of understanding how grades work and what they can and cannot show.

View Tom Bramley's paper.

Exploring alternatives to grades

Other methods are used in assessment as an alternative to grades.

For example, scaled scores, such as those used for key stage 2 national curriculum tests (SATs) in England, convert raw marks into a consistent numerical scale. This allows comparisons across different test versions and gives a more discrete measure of candidate performance. Learn more about them on the GOV.UK guidance page.

If you're interested in scaled scores, the next blog in this series will explore how they work and how they can be used as an alternative to grades.

Final thoughts

Grades continue to play a key role in education. They are widely understood, easy to communicate, and help maintain consistency in reporting across different years and contexts.

If you would like to explore how grades are awarded and how scaled scores are used in assessment, consider enrolling in A103: Assessment Data and Statistics. This course was developed with input from James and offers practical insight into key concepts in modern educational assessment.

Blog author

James Beadle has worked for Cambridge University Press and Assessment since 2020. He is currently a Senior Professional Development Manager at the The Assessment Network, where he designs and delivers training in assessment for a wide range of customers, including schools, universities, and education ministries.

James Beadle has worked for Cambridge University Press and Assessment since 2020. He is currently a Senior Professional Development Manager at the The Assessment Network, where he designs and delivers training in assessment for a wide range of customers, including schools, universities, and education ministries.

In his previous role as an Assessment Manager, he was responsible for the management of several high-stakes international mathematics qualifications.

Originally trained as a mathematics teacher, he has worked in a wide range of contexts, both in England and internationally.

He holds a master's in Mathematics Education from the Institute of Education, University College London. As part of his master's, he carried out a comparative analysis between the Shanghai Gaokao, A Level, and IB Mathematics papers.

He is currently a tutor on the University of Cambridge Postgraduate Advanced Certificate in Education Studies: Educational Assessment course.