Read time: 8 minutes

Assessment literacy is about more than understanding how assessments work. It’s about knowing what they’re for, how they should be used, and why that matters to everyone involved—teachers, students, families, and policymakers alike.

In our survey, assessment professionals from various sectors told us that challenges arise from a lack of shared understanding:

“We sometimes struggle to convince families of the importance of formal assessment for young learners.”

“We find assessments are being used for purposes they weren't intended for.”

At Assessment Horizons 2025, we invited our speakers to share insights on how improving assessment literacy can help overcome these barriers.

The 'marginal' gains of improving assessment literacy in schools

How do trainee teachers feel about assessment? George Vlachonikolis, Head of Teaching and Learning at Headington Rye School and an Assessment Network ambassador, has worked closely with this group. He suggested that small shifts in school culture can significantly improve assessment confidence and understanding.

Taking into account the varied academic literature on the subject (e.g. Rick Stiggins original definition in the 90s), George summed up his view of assessment literacy as:

- Knowledge of the principles of good assessment

- Ability to put those principles into practice in the classroom

- In order to improve student learning

George felt that much of the academic literature around assessment literacy (including John Popham, Xu et al, Volante et al) unfairly paints trainee teachers as being ‘assessment illiterate’.

George felt that much of the academic literature around assessment literacy (including John Popham, Xu et al, Volante et al) unfairly paints trainee teachers as being ‘assessment illiterate’.

He argued that most trainee teachers have a strong knowledge of good assessment principles, but that sometimes they can be ‘assessment inhibited’:

“There could be barriers to putting those assessment principles into action. Maybe it’s an emotional barrier because they're anxious about what the outcome of those assessments might be? But it also might be a systemic barrier, for example they might not have a supportive mentor showing them what good assessment looks like.”

George had a number of suggestions for ‘marginal gains’ that schools could make to reduce these inhibitions:

- Appointing dedicated assessment mentors could be a “game changer”

- Bringing more formative assessment into lesson planning (in particular, the use of quick low stakes understanding checks)

- Encouraging oracy—getting students to talk through ideas and check understanding

- Creating CPD libraries to share assessment best practices early in teachers’ careers

George concluded: “It's not about re-educating teachers. It's not about going through the principles of good assessment with them again and again and again. But it is about removing these frictions that I've talked about: the emotional barriers and the systemic barriers that might exist in terms of putting those principles into action in the classroom."

The student voice on assessment

How can students develop their understanding of assessment principles?

Our Assessment Horizons keynote group from University College Dublin presented an innovative project that empowered students to develop their critical thinking around assessment.

The Engineering faculty team came up with a podcasting competition that invited students to assess their academic assessments in light of the opportunities and challenges brought about by AI.

The students examined closed book exams, reflective assignments, online exams, lab reports, individual assignments and group projects in their ‘Bridges and Bytes – The Student Voice on AI and assessment’ series.

Dr Simon Child, Head of Assessment Training said: “We thought this project was an excellent example of empowering learners to assess assessments in light of the changes brought about by AI. Through undertaking this project they have created some sophisticated, timely and rich insights on the purposes and limitations of different assessment types.”

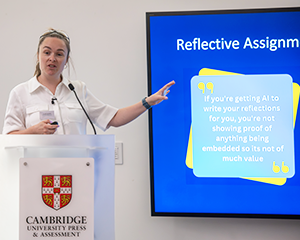

Professor Jennifer Keenahan shared a first year’s thoughts on reflective assignments as a form of academic assessment:

“Reflective assignments are often touted as being a really good opportunity to get to the heart of what students have learnt. But of course, sure, AI can create these in a heartbeat. The point that one student made was that if you're getting AI to write to reflective assignments, then you're not showing proof of anything being learned or anything being embedded.

He said: “In trusting reflections solely to AI, I could potentially remove humanity's ability to produce great works. AI can support reflection by providing insights and prompting questions, but it lacks the consciousness and the lived experiences that shape human reflection.’"

Simon continued: “We know from the research that when learners develop assessment literacy or ‘feedback literacy’ (as it is sometimes known in formative assessment) they are in a better position to recognise their active role in the assessment and feedback process, and can focus their attention on how it contributes to their own future learning.”

Parents as assessment stakeholders

Parents also play a vital role in shaping how assessment is understood and used in schools. In a different session at the conference, Simon shared the impetus behind a new research project that addresses a different assessment stakeholder group: parents.

His presentation ‘What do teachers need to know about assessment to support their children’s learning?’ unpacked a project The Assessment Network team have been working on with Dr Ourania Ventista and colleagues at the Department of Primary Education at the University of the Aegean in Greece.

The team are keen to learn what role parents play in affecting the school’s overall assessment culture. They've been interviewing secondary age parents in the UK and Greece to understand the level of engagement the parents have with the school and their child’s learning. The second part of the research determines how much knowledge and understanding of assessment concepts these parents and caregivers have - and how these are acted on in relation to their child’s learning.

Simon explained: “Educators aren’t making assessment decisions in a vacuum, they are doing so within the assessment ‘culture’ that they live and work in. Parents play an important but sometimes overlooked role in the eco-system of a schools’ assessment culture.” The team will share the results of the survey later this year.

Creating a culture for assessment literacy to thrive

Assessment Network Ambassador Victoria Merrick led an insightful workshop session that once again highlighted the importance of a school or organisation's ‘assessment culture’. She emphasised the value of listening to teachers, students, and parents to uncover overlooked barriers in developing a positive assessment culture.

Victoria shared some examples she'd observed as a former school leader and education consultant. A key insight was the unintentional consequence of change in this space: "When stakeholders aren't actively involved in the design and development of new assessment plans and supported to engage fully in understanding the resulting data, this can inadvertently fuel misconceptions. There is a very human response to fill spaces of uncertainty and lack of knowledge, with fear - a fight or flight response. There is then a risk of anxiety and division rather than collaboration."

“What is needed is broad communication and shared understanding. This then supports efforts to refine assessment strategies."

Simon Child expanded on this by referencing the growing idea of 'assessment identities', a concept led by educational researchers like Gavin Brown at the University of Auckland and Anne Looney at Dublin City University. This refers to the beliefs and assumptions we all carry about assessment, shaped by our individual experiences.

“Whether you’re a teacher, student, parent or examiner, these beliefs influence how you make assessment decisions. By improving assessment literacy, we strengthen those decisions and create better learning outcomes.”

Members of The Assessment Network at Cambridge get free online access to Assessment Horizons and a range of benefits.

Learn more

Illustration: Rebecca Osborne